The Abroad and Aback of

The Experience

Though a storyteller through artwork since his earliest memories in life, Charles Shearer did once set aside that cornerstone of his identity. It was the five years in which he lived in South Korea as a foreigner and a teacher, traveling elsewhere around the world whenever time allowed, and experiencing real adventures and relationships. He therefore lost all need to invent fictional people and scenarios anymore; the yet unfinished graphic novel "Li'l Lynn" languished in a footlocker in Charles's native United States, with no intention of the project ever seeing completion, let alone the light of day again. He intended to instead continue pursuing fulfillment by remaining abroad and gaining a family of his own to raise.

But life doesn't care what plans we have for it.

Charles instead ended up jobless and homeless, in that country which no longer wanted him. Discouraged (to say the least), he returned to America, where he soon picked up his old identity but with new inspirations. The three main volumes of "Runaway Weer" came to life during this miserable era of intense yet thankless work and long yet unrestful sleep. The eponymous Aspynn Weer the runaway comes to create new sides to herself, and is forced to account for her choices and actions, in a story which reflects Charles's own prosperity, disaster, and soul-searching thereafter.

Allusions and Influences

More-so than in his other avowed and published projects, "Runaway Weer" is a testament to Charles's appreciation for a number of famous stories which ask endlessly debatable questions about the deserving of guilt and the cost of vengeance: the novel "The Scarlet Letter" by Nathanial Hawthorne, the tragic play "MacBeth" by William Shakespeare, and the epic poem "Paradise Lost" by John Milton; such stories are driven by the fatal flaws of those who step out of bounds, are vilified for it, and have nowhere to go but deeper down the path of infamy.

The non-fiction book "Daughters of the Earth: Lives and Legends of American Indian Women" by Carolyn Niethammer (Simon and Schuster Paperbacks 1977) played an unexpected yet essential role in shaping the treatment of gender and fertility in "Runaway Weer": that the humans Aspynn and Lindynn are adolescent females in the 'present' narrative is both pivotal for the functioning of the plot and inextricable from the primeval setting, serving as a work of fictionalized anthropology about what is original to humanity and what we instead adopted from 'others.'

The nature of "Li'l Lynn" and "Runaway Weer" being parallels (or bizarro versions!) of each other is largely thanks to a number of foundational comics exercises which had been taught by Professor Bob Pendarvis [at that time] at the Savannah College of Art and Design: making works which are 'the same' yet also paradoxically as different as possible from each other. The purpose of such exercises is to make a creator more conscious of and deliberate with their own choices.

A Foregone Conclusion

In a sense, "Runaway Weer" had all happened before: it is, in addition to all which is described above, also a complete re-imagining of and replacement for Charles's college-era comics series, titled "Fyre an' Ayes." The two series thus play out as bizarro versions of each other, and since "Li'l Lynn" had originated as a prequel to that now delisted college work, the two avowed and published ones can not help but share some similarities: it is as if the prehistoric Aspynn Weer and Lindynn Herr meet again as the modern era children Ashley Weir and Lynn Herr, across continents of space and millennia of time.

For some reason which can not be explained, the very first speculative writing for "Runaway Weer" was done while Charles was still living in Korea, more than a year before any sign of disaster. Those text files contain the first drafts for what would become the Volume 1 stories "In Exile" and "In Custody," specifically, as well as a general sense of how the three races/peoples are distinct from each other. Adaptation of "Fyre an' Ayes" seems to have been the main point, even at that earliest and most flimsy state of development. At the time, however, Charles no longer had access to viewing any of his previous projects, and instead had to rely on memory. Making "Runaway Weer" into its true, finished form therefore required enduring further the very sort of experiences which the series itself is about: the ebb and flow of life, of the unthinkable occurring nevertheless... and that however far away you go to find yourself, yourself may always find you.

Finding the Look

Volumes 1, 2, and 3 were entirely written and penciled before any serious ink-drawing experiments took place. A number of decisions had to be made ...which was challenging enough... but they would then need to be applied as consistently as possible through the entire ink-drawing process thereafter. In other words, good decisions early-on would be rewarding again and again, whereas bad decisions made at an early stage would keep being punishing.

The goal was to achieve a different look than "Li'l Lynn" had, in terms of facial features.

Lindynn's hair 'color' was a point of long indecision. Took some time for 'black' to look right.

Having to decide the limits of 'coloration' differences between members of the same species.

Experimenting with fabric textures/weaves, as these were a point of differentiation

between human-made and imperial-made.

Different types of dip-pen might make similar-looking marks, but they perform differently in the hand.

Trying to finalize the look and the technique, heading into ink-drawing volumes 1, 2, and 3 together.

Whether to blacken the gutters (i.e. space between panels) was another point of long indecision.

Final page of ink-testing in the sketchbook, trying to visually distinguish Aspynn and Lindynn

from each other, especially while both are in imperial uniforms.

The Production Process

For continuity and composition, steps have to be followed in a certain order: conceiving, thumbnails-as-writing, gridding, penciling the lettering, penciling the drawings, inking, practical corrections, scanning, digital editing.

The writing and visuals were both mostly planned via 'thumbnails' in a sketchbook.

It was sometimes helpful to make entire-page thumbnails such as this one.

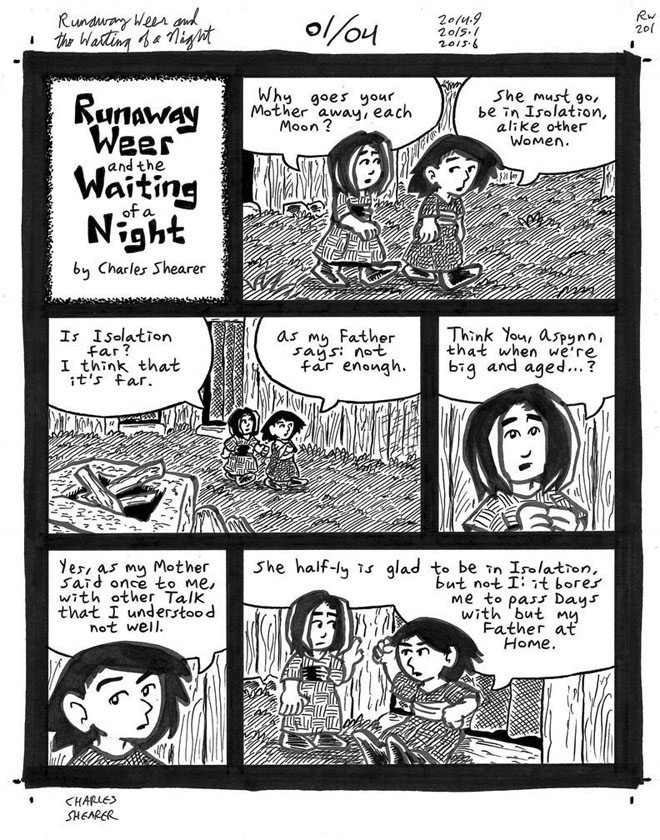

The result of the original art process: ink drawings on Bristol board, with the penciling erased.

The archival notes suggest: penciling in 2014 September, ink-lettering in 2015 January,

and ink-drawing in 2015 June. Very common for drawings to have such long production gaps.

The result of post-production: clean, consistent images for printing and publishing.